One of the challenges of conflict is that creative teams or workplaces are often fully engulfed long before they’re even aware something’s happening. Therefore, a crucial first step in dealing with conflict is to simply recognize the signs it may be occurring. This is easier than it sounds, but it’s critical because the earlier an emerging conflict can be detected, the sooner steps can be taken to resolve or manage the issue(s) effectively and prevent further harm.

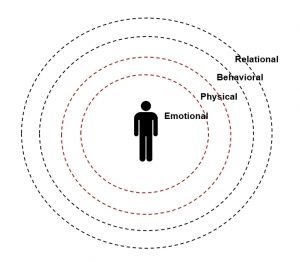

There are four categories of warning signs: emotional, physical, behavioural, and relational. Think of these as concentric circles spiraling outwards from within and progressively manifesting externally if unnoticed or left unchecked. Each successive set of indicators, if ignored, inevitably leads to the next level, with ever-increasing consequences.  It’s like your cat trying to tell you it’s feeding time, going to greater lengths to get your attention, only it’s not funny (and hopefully will never wind up on YouTube).

It’s like your cat trying to tell you it’s feeding time, going to greater lengths to get your attention, only it’s not funny (and hopefully will never wind up on YouTube).

Let’s examine what each of these sets of signals mean and why they happen. The analysis can provide useful insight into the individuals involved in a conflict at a personal level. In observing and interpreting the warnings we can apply the knowledge not only to ourselves but also to others (namely, our colleagues) and take appropriate, timely action.

Emotional signs

The first indications of a problem in a working relationship are internal: our emotions. Feelings are a reliable barometer that things aren’t OK. If my normal state is one of comfort, happiness, relaxation, engagement, calm, and/or contentment, then it’s easy to tell when I move away from that baseline. I can usually identify or describe any uncomfortable feelings I’m having. When trouble is brewing between myself and another person, this discomfort is going to be the first sign that all is not quite right. We may have a conflict, which itself is simply a signal that something needs to change, occurring when something we care about is about to be affected in some way. Time to pay attention!

Feelings will, of course, vary according to each individual involved and each situation. For example, a situation that might seem humorous when it happens to someone else is usually not so amusing when it happens to you. The intensity of the feeling might also vary from one instance to the next. You might feel confused by multiple feelings occurring simultaneously. The range of possible emotional reactions is virtually limitless; there is no definitive feeling or combination of feelings. The bottom line is that any emotions at all outside the normal comfort range are probably a warning.

As such these feelings should not be ignored or repressed. Some find it easy to overlook them because society prefers that we avoid expressing unpleasant feelings. We may downplay what’s going on inside when we experience them; we put on a brave face and say everything is “fine” when we know it’s not. Whether or not you choose to divulge them, it’s important to recognize that these feelings are a kind of internal gauge of whether or not the person you are dealing with, or the situation you are in, is psychologically healthy and safe. They’re like the VU (volume unit) meters on a mixing board: when they’re pushing into the red zone, you know the signal is “clipping” and you need to do something because unwanted noise and distortion are being introduced into the signal. If your emotional VU meter is tipping into the red when you are with a particular person or in an uncomfortable situation, that’s your signal to act.

Sometimes this means temporarily stepping away from the person or situation causing the discomfort, taking a time-out, and putting some physical or emotional distance between you. That may be all you need for your feelings barometer to return to its baseline and to once again feel calm, relaxed, engaged, happy, or whatever your normal state happens to be. If that’s genuinely the case — after a good night’s sleep the discomfort is truly gone and not merely repressed— then you may not actually have conflict. But if the feelings persist, it could mean there is a problem between you and that other person. Avoidance or masking feelings with food, distractions or addictions won’t help. Trying to “rise above” or “be professional” about the uncomfortable situation are among the countless ways to cope with unpleasant feelings. But when there is a genuine conflict between two or more people—one in which the relationship is being challenged (if not damaged) in some way—then the feelings are not going to go away on their own.

Physical signs

If the emotional warning signs continue unheeded, another natural protective mechanism kicks in. The manifestation of physical symptoms is your mind and body’s way of issuing a more urgent set of signals that are more difficult to ignore.

Again, everyone will experience physical warning signs of conflict differently, but some are quite common. There are those that seem trivial, such as nervousness or sweaty palms. Others are more noticeable and worrisome, for example, difficulty in sleeping. Depending on the individual, the opposite may also be true: you may find that you begin to sleep more than usual, either as a way of avoiding the conflict or recovering from the stress and anxiety it brings. These are two opposite but equally valid physical signs that are more evident than emotions, precisely because they affect not only your mind but your body. Frequent headaches can be among the common physical warning signs of conflict, as are subconscious activities like smoking, eating, or drinking more than usual. These strategies provide bodily sensations to mask the unpleasant emotions we may be experiencing, if only temporarily. (Here the standard disclaimers apply: always check with your doctor if you’re experiencing physical symptoms of any kind; there may be other physiological causes that should be ruled out.)

Not surprisingly, the physical indicators have their own knock-on effects, especially when piled on top of the emotional stuff. Consider the consequences of eating, drinking, or smoking to excess, for example. The short-term results may be stomach aches, hangovers, or smoker’s cough, and the longer-term impacts can be far more severe, even deadly. There are many possible causes of physical ailments, one of which is that the original problem hasn’t gone away of its own accord. The physical manifestations are harder to ignore so that you’ll finally be moved to do something about it before worse things happen. Even sleeping too little or too much can have consequences extending beyond personal health. In workplace scenarios, one typical result of unmanaged conflict is an increase in chronic lateness or absenteeism.

Behavioural signs

If the physical warning signs of conflict go unheeded and the core issue remains unaddressed long enough, the next set of signals kicks in. These behavioural indications are overt and more readily observed by others. The subtle logic of the psyche’s strategy is this: if you can’t (or won’t) take care of yourself, you will get someone else to do it for you.

How does your subconscious enlist others in your conflict caretaking? Here, too, the range of possibilities is wide, but examples of the more common tell-tale behaviours might include a normally calm and serene person appears agitated and on edge; a typically patient individual becomes short-tempered and easily triggered; someone who is otherwise engaged and outgoing begins withdrawing; and so on.

You might notice, for example, that a team member who usually goes out socially after work starts making excuses to go right home, or one who normally participates in team discussions and decision-making stops contributing. They may just shrug and say, “Whatever. I don’t care.” Conversations tend to become more difficult, more tense, more strained. Electronic communication may take much longer to get answered, if at all, or responses are more tersely worded than usual. Eye contact may be avoided. You don’t need to be an expert at conflict resolution to detect behavioural changes; the untrained eye can usually spot the signs. We just don’t always recognize them as indicators of conflict.

Abnormal behaviours could be symptoms of another issue or problem, but you won’t know for sure unless you ask. Even then, they may not respond (at least not immediately or candidly), but a change in communication style is sometimes a cry for help in disguise. Unusually difficult behaviours may be indirect and inarticulate invitations to assist, but nonetheless that’s what they are. Uncharacteristic conduct is a way to draw others in because it inevitably affects them one way or another.

Relational signs

If left too long, the logical consequence of behavioural issues are the relational warning signs that manifest. The relational signs are the most difficult of all to ignore because they’re the most public. Now it’s not just the individual who is affected but others in the relationship. Like the previous three categories they may also appear different for everybody, since no two individuals, conflicts, or situations are identical.

Still, you can spot some common relational warning signs. A person feeling uncomfortable or in conflict may begin avoiding specific people, primarily the person(s) with whom they are in conflict. In a work setting, this might mean he or she takes a different route to the cafeteria or the washroom in order to bypass the other party’s office. They might ask the boss to put them on a different team to reduce the likelihood of interaction with the other person. There are many variations on this avoidance behaviour that people typically employ when in conflict, but they might be hard to spot at first precisely because “out of sight is out of mind.”

Generally, the relational warning signs are easier to detect because they impact multiple individuals, entire teams or companies. As with the other three sets of warning signs they will vary greatly, from deliberate unresponsiveness to singling others out for criticism or verbal attacks, belittling others’ perspectives and contributions, or shooting down their ideas. There may be open disagreement, challenge, argument, or outright hostility. Other nonverbal cues may include eye-rolling, crossing arms or other defensive postures, and deliberate distractions. There may be rumour-mongering, idle gossip, or complaints to others in an effort to win sympathy and support. You can probably identify other examples from your own experience.

Clearly, the relational symptoms affect not only the person with the initial conflict symptoms, but they also impact the others in the group, team, or company. Innocent bystanders often become embroiled. Stakes are much higher by this stage, and if things don’t get resolved soon the whole workplace gets involved one way or another.

Pay attention now, or the pay consequences later

In the midst of a conflict, it’s hard to stop to take proper stock of the situation or retrace steps to figure out how things devolved to the present state. But in learning to recognize these early warning signs, you can remain alert to whatever may be happening right now that requires immediate attention. The internal warning signs tell you it’s time to take care of yourself in some way – often just by asserting your needs – and the longer you put off taking action, the more intense they become. Invariably they will become more outwardly noticeable, which can only cause further discomfort or damage.

It’s understandable that many are uncomfortable talking candidly about their feelings with colleagues or co-workers, because of the additional sense of vulnerability it can bring. Some are only comfortable discussing their feelings with therapists or other professionals, if not with life partners. (Some find even that hard to do). But feelings should be acknowledged and honoured, if not celebrated, because they play a vital role as part of an early warning system. The initial discomfort may be unpleasant but the alternative is greater pain and distress for everyone in the long run.

It’s like your cat trying to tell you it’s feeding time, going to greater lengths to get your attention, only it’s not funny (and hopefully will never wind up on YouTube).

It’s like your cat trying to tell you it’s feeding time, going to greater lengths to get your attention, only it’s not funny (and hopefully will never wind up on YouTube).